In this class you will be introduced to different texture of watercolour paper. There are 3 types of textures that you can find on the package:

For people with a good imagination it is easy to compare different types of paper with asphalt pavement.

The hot pressed paper surface looks like as a freshly laid silky asphalt, although you need to understand that it is not smooth and clean as a glass surface. It still has a few very shallow slightly visible cavities and holes. It is called a “smooth tooth” surface. This is referred to as “hot press” because the cylinders that are used to press the paper during the manufacturing process are heated. Hot press paper gives you a very smooth effect of fine realistic painting. It used for portrait, botanical illustration and wherever you want to have the effects of clean transparent washes.

The cold pressed paper you can compare with the older asphalt. It is not rocky yet, but you can clearly see a lots of cavities and holes. This is referred to as “cold press” because the “cold” unheated cylinders are used to press the paper as it is manufactured. The Cold pressed paper is the most commonly available paper in the market. I am sure you have used it at least once in your life. The curves of the texture provide cavities to hold paint pigment in place. The texture gives you enough roughness to be good for all styles of watercolour paintings.

The texture of the rough paper you can compare with a gravel road that has never been maintained. The cavities and holes are very visible. Rough papers are not produced by cylindrical pressing. They are flat-pressed mechanically or not pressed at all. The result is a very heavy “tooth”. It is usually used for landscape paintings where the effect of rough textured surface will be more visible. This is my favourite type of paper. I find it is most fascinating to use because you do have not any idea what results you will get.

In this class we are going to practice fast landscape sketch using only three colours; Burnt Umber, Paynes Grey and Ultramarine. Although using Yellow Ochre, Olive Green and Burnt Sienna is optional.

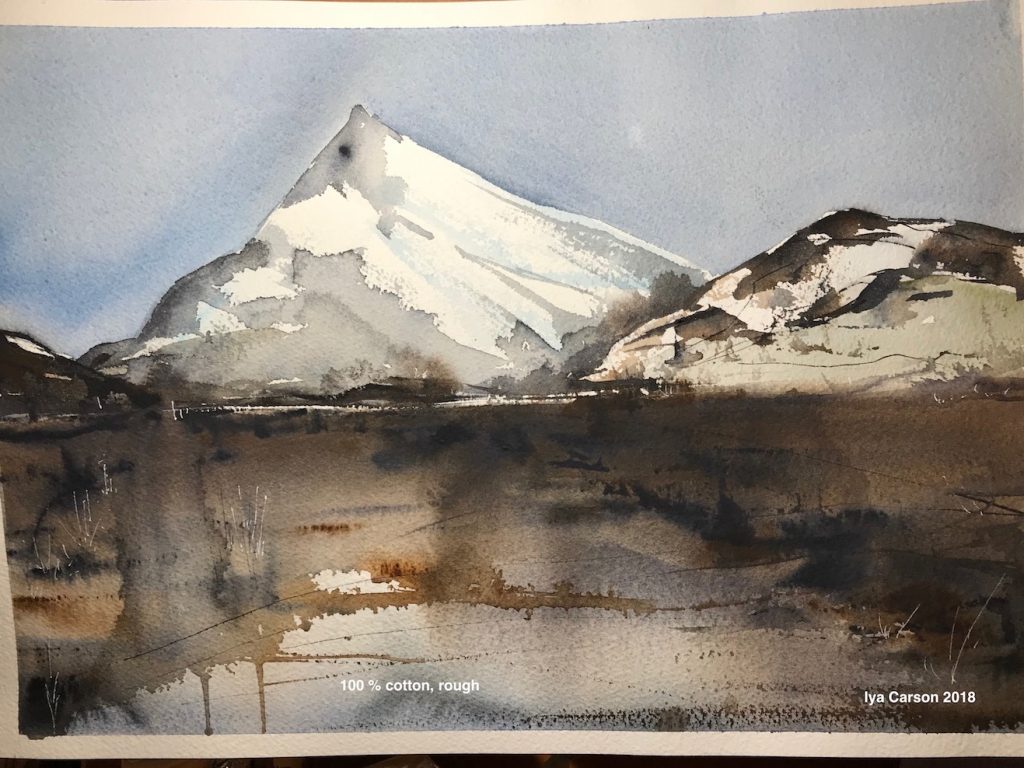

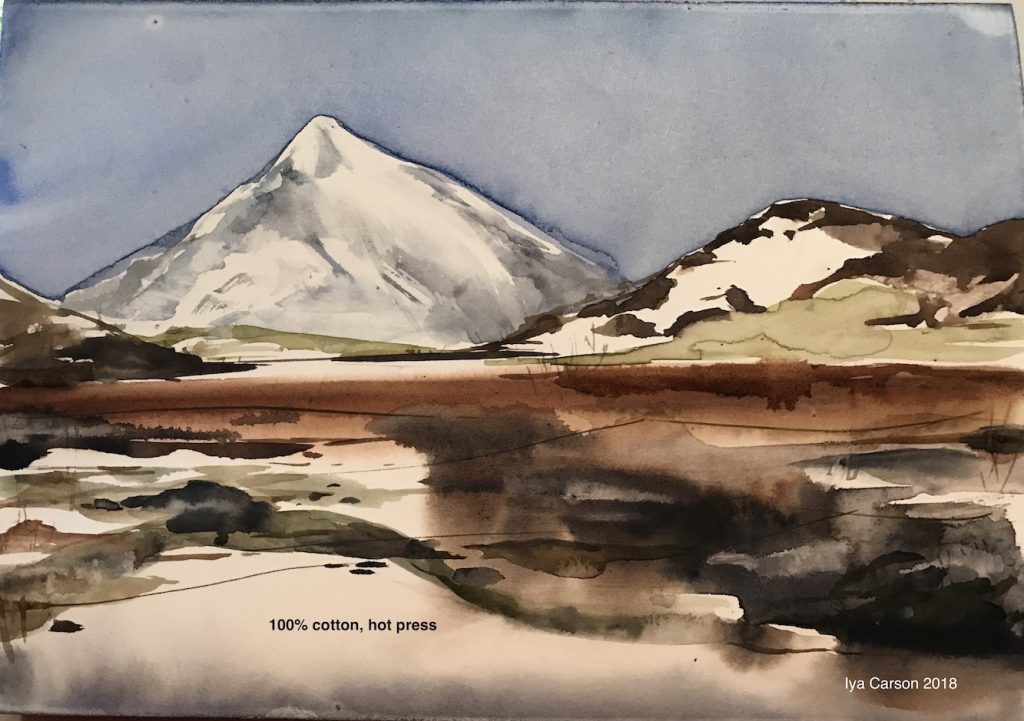

Please compare the result of the same painting done on paper with different surfaces. You can see the results in this gallery.

Cellulose paper

Arches, 100% cotton, Cold Press

Arches, 100% cotton, Rough

Stonebridge, 100% cotton, hot press

Materials used for the video demonstrations: Watercolour paper - Strathmore 400 series, 100% cellulose - Fabriano, Rough, 100% cotton - Arches, Cold Press, 100% cotton - Strathmore LANA, Hot press, 100% cotton Watercolour brush - Flat brash, 1 1/2, Japan - Flat brash, size 3, Biaekl 256Flat - Mop brush, 10 mm, Paul Rubens size 6 - Flat brush, 3/4, escoda - Calligraphy brush, 3 mm - Liner, Grambasher, 30mm Watercolour paint, Van Gogh - Paynes Grey - Ultramarine - Burnt Umber -Burnt Siena and Yellow Ochre are optional White paint - Bleed Proof White, Dt.Ph. Martin's - Acrylic marker, UNI Posca, 1 mm Plexiglas board Cardstock board Drafting tape Water Paper towels

Video tutorial

Please note, on the image about the heavy visible pencil outline of the central mountain was created specifically for the video tutorial. When you will be ready to do your pencil sketch for this watercolour practice, please don’t press your pencil hard. The light almost invisible lines will be enough.

Exercise 1. Brush work practice

In this exercise you will be practising brush strokes to create mountain silhouettes and illusion of the wet sand. My recommendation first try a few times your brush stokes on cellulose paper, then use a good quality cotton paper.

You can use one sheet of paper divided into six blocks with drafting tape, or you can use six small pieces of paper. Tape your paper to a heavy card-stock board.

In this video tutorial the cellulose paper was used.

Exercise 2. Painting algorithm

In this video you will be learning the algorithm of painting process. You will need a printer paper and a pencil.

Legend: ULTR - Ultramarine PG - Paynes' Grey BU- Burnt Umber

Painting

Please watch the videos first, and then practice your paintings. Do it as many times as you want.

References for homework inspiration

OVAS NL L3 Reference 2

OVAS NL L3 Reference 3

BONUS

Paint Library

I decided to add this information because you might start to feel more comfortable with the different types of brushes and watercolour paper, so it is time to learn about your paints.

To create your paint’s library lets learn how to read the labels of the watercolour paints.

MARKETING NAME

To understand this we need to be aware of the difference between the terms ‘paint’ and ‘pigment’. The pigment is what gives the paint its colour. It will derive either from a ground organic substance, or a synthetic substance that is chemically produced. The paint is the combination of that pigment and a binder (such as oil, acrylic polymer or gum arabic) which holds the pigment together and dries into a film when you apply the paint to your paper or canvas. There may also be other additives included in the paint mixture such as drying agents or fillers to bulk the paint out. These additives do not have to be declared on the paint tube. Arabica gum, but the name rarely tells you which pigments are inside.

The name on a paint tube is often the most misleading part of the label. It’s chosen by the manufacturer for marketing purposes and doesn’t necessarily reflect the actual pigments used. Paint consists of pigment (the substance that gives it color) mixed with a binder like Arabic Gum.

There is a standardized system, called the Colour Index, which identifies pigments, but many paints don’t use these names on their labels. Instead, companies may come up with attractive or simple names, like “Pthalo Turquoise”, even if the paint is made from a blend of pigments.

Knowing the pigments matters because different pigments behave differently. Without accurate information, you can’t predict how the paint will perform or last over time. Paint companies also reuse names of obsolete pigments, like ‘Payne’s Grey”or “Neutral Tint”, substituting other pigments but often omitting the “hue” label that should indicate these are approximations.

SERIES NUMBER

Another piece of coded information we are given on the paint label is the ‘series’ number. This is a straightforward bit of information that tells you how much your paint tube is likely to cost. Manufacturers generally group their colours into five different price brackets or ‘series’. ‘Series 1’ paints will be made from the cheapest pigments and will be the least expensive in the range. Hue colours and most modern synthetic colours like our Pthalo Turquoise will be found in this band.

It doesn’t necessarily follow that a series 1 paint cannot be as good as one from a more expensive series – some pigments are just much easier and therefore less costly to produce or process. ‘Series 5’ paints are the most expensive and can cost well over twice as much as those in the Series 1 bracket. They are more likely to be derived from single pigments which are difficult and expensive to produce.

COLOUR INDEX NAME or PIGMENT NUMBER

Turning over the tube, we finally find the only really useful information about what’s actually inside. This paint is listed as containing pigments ‘PG7 and PB15’. This information relates to the Colour Index which is a standardised naming system regulated jointly by the British-based Society of Dyers and Colourists and the American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists. You can find a useful version of this database for free here.

The Colour Index name is actually both an officially assigned name, and a code. The code is comprised of some letters and a number. The first letter will normally be a P which denotes that it’s a pigment (rather than a dye, for example) and then there will be another letter denoting the colour category: R for a red, O for an orange, Y for a yellow, G for a green, B for a blue, V for a violet, Br for a brown, W for a white, Bk for a black and M for a metallic pigment. If a pigment derives from a purely natural source it may start with an ‘N’ for ‘natural’ instead of a ‘P’.

Following the letters, there will a number which defines the individual pigment within that colour category. For example the paint Payne’s Grey from Van Gogh (the first paint tube from the left side) includes two pigments: ‘PBk6’ which is the number for the black pigment Carbon Black, and ‘PV19’ which is the code for the violet pigment Quinacridone Violet.

You may notice that this particular tube of paint doesn’t follow best practice and omits to list the official names of the pigments, giving only the code instead. This is more common on European-manufactured tubes than American ones and it’s frustrating since the consumer can’t be expected to easily identify a pigment from its index code without looking it up.

PAINT VEHICLE

The term ‘vehicle’ refers to the ‘binder’ which is the medium that’s been mixed with the pigment. It’s the substance that has been added to bind the pigment together and to form a film that holds it in place. In watercolour the binder is usually is gum arabic.

LIGHTFASTNESS RATING

The lightfastness rating on a paint tube which is supposed to give you an indication of how resistant the colour will be to fading from light exposure, is represented in different ways by different manufacturers. The most common way to represent lightfastness is with roman numerals :

I. Excellent lightfastness. The pigment will remain unchanged for more than 100 years of light exposure with proper mounting and display. (Suitable for artistic use.)

II. Very good lightfastness. The pigment will remain unchanged for 50 to 100 years of light exposure with proper mounting and display. (Suitable for artistic use.)

III. Fair lightfastness (Impermanent). The pigment will remain unchanged for 15 to 50 years with proper mounting and display. (“May be satisfactory when used full strength or with extra protection from exposure to light.”)

….and so continues down to V (very poor lightfastness)

Other rating systems may merge some of these categories to produce a system that divides lightfastness into just three categories with ‘I’ representing ‘Durable’, ‘II’ representing ‘Intermediate’ and ‘III’ representing ‘Fugitive’.

Some companies use different icons for lightfastness. Royal Talens uses a system of noughts and crosses (o, +, ++, +++) which runs in the opposite direction so that o is the least and +++ the most lightfast. Schmike uses a star system which also runs in this direction, with ★ indicating the least lightfast paint and five stars indicating the most lightfast.

In short, you’ll need to consult the manufacturer’s website to work out how to read their particular system, and to find out whether they are relying on the ASTM ratings or on potentially unreliable information given by the pigment manufacturer, or whether they are actually testing their own paints themselves. Very few paint companies test their own paints for lightfastness. Daniel Smith and Schminke are amongst the few who do so.

OPACITY

Some pigments are much more transparent than others. On the tube of Neutral Tint, Van Gogh indicates the level of transparency of the paint with a little empty box . This indicates that the colour is extremely transparent. A white box with a diagonal line through it would mean semi-transparent, a diagonally-divided half white/ half black box is used to indicate semi-opaque, and a completely black box would mean it was totally opaque.

Manufacturers find a variety of ways to indicate the degree of transparency/opacity of their colours. Sometimes a little ‘wheel’ icon is used. Other products employ a lettering system whereby transparent colours are marked ‘T’ and semi-transparent as ‘ST’, whilst opaque colours are marked ‘O’ and semi-opaque ‘SO’. Other manufacturers will keep things simple and just write ‘Opaque’, ‘Semi-Opaque’ and so on.

HEALTH AND SAFETY

Most paints will indicate their compliance with American standards for paint labeling as regards health and safety. These codes are voluntary but have been widely adopted. On the photo you can see different labels declared on the tubes labels. Firstly, it contains a written statement that the paint ‘Conforms to ‘ASTM D 4236’. This refers to ASTM’s Standard Practice for labeling Art Materials for Chronic Health Hazards guidelines. All this really means that any potentially hazardous ingredients or risks posed by the ingredients will be clearly labelled. That you can find on the Shminske tube (middle tube) statement that the product may be harmful if swallowed and should be kept out of the reach of children.

On the first two tubes you can see the declaration seal of the Art & Creative Materials Institute or ‘ACMI’ which is an American non-profit association of art and craft supplies. An ACMI Approved Product Seal on a paint label certifies that the paint is non-toxic both children and adults and “contain no materials in sufficient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans, including children, or to cause acute or chronic health problems”.

Inside this seal will be either a large ‘AP’ (for ‘Approved Product’) or ‘CL’ (for ‘Cautionary Labeling’). If there’s a CL label then underneath you’ll see a specific written warning about health problems posed by the pigment.

CREATING THE PAINT LIBRARY

You can use any template to create your paint library. As you can see on the photo I am using a simple design whit a bottom block covered with paint and a top block where the all information about a tube is collected. I would recommend to you to use a good quality paper.

On this photo you can see all paints that we are going to use for this course.

Student’s work